The Cree Hunting Drum

My sister Eva gave me this hunting drum for my 19th birthday – a long time ago! Haha. It’s a replica of the traditional Cree hunting drum that Cree hunters used over many generations to sing songs about their love and respect for the animals they hunted.

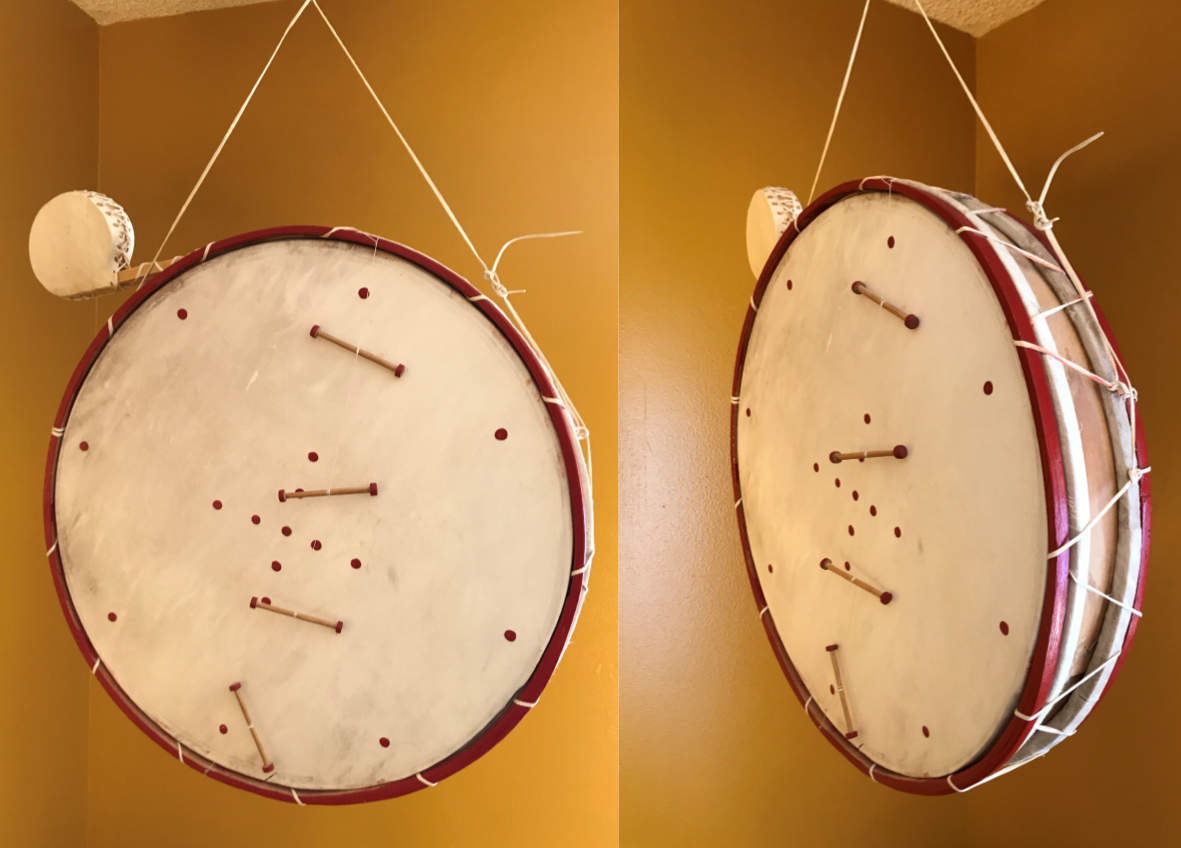

Eva had it made by someone in the Cree community of Mistassini, Quebec, where she worked at the time. The drum is made out of wood, caribou or moose hide stretched across the frame. It has red dots on it, and my understanding is that the paint is to replicate the red ochre our peoples used many centuries ago on their faces and on items such as snowshoes and paddles.

The drum has a deep sound to it. I’ve heard other, bigger, drums of this type that sound very deep and resonate really well. The hunter would tap the drum skin with his hand or maybe use a shaker like the one attached to my drum. It, too, is a small, handheld version of the drum, but with a shaker sound.

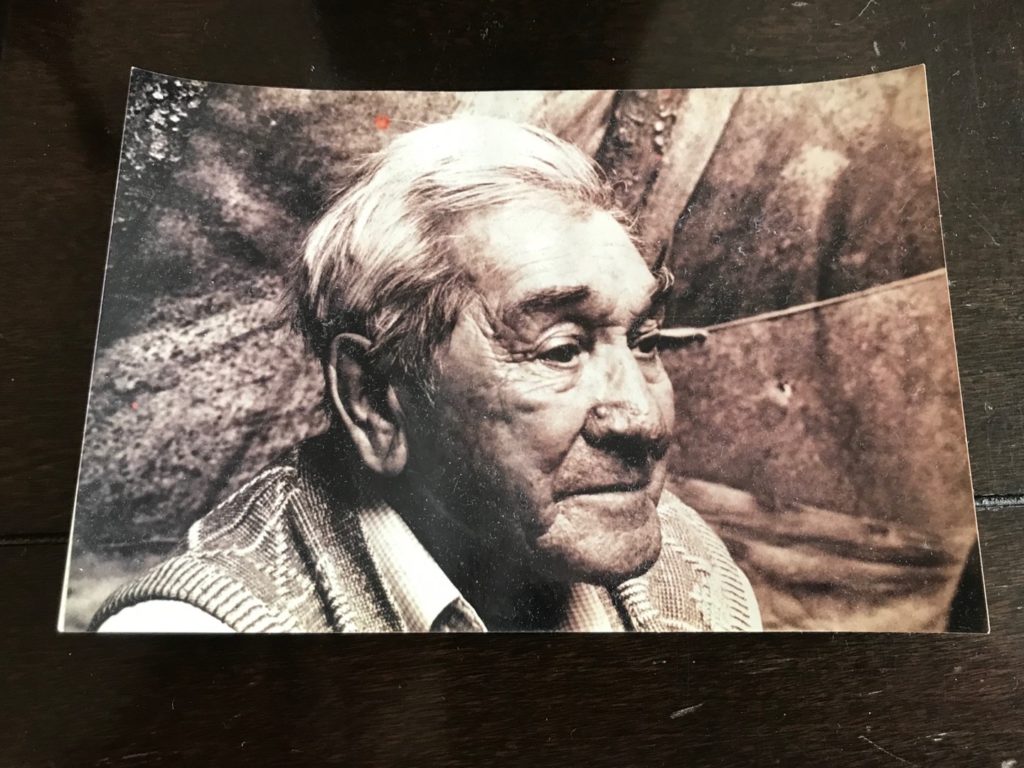

My father collected hunting songs when we lived in the Eastmain, Quebec area, and had recordings that I heard as a young boy in Moose Factory. The old men singing on my father’s recordings fascinated me, and by that time, 1970s, it was only voice and maybe fingers tapping a table or their lap.

Over time, missionaries that arrived during the Hudson and James Bay fur trade frowned on the drum and the songs. So the drum disappeared, and the songs were only sung in private or on the trap-line, where hunters continued to sing about the animals, fish and birds that they harvested. It was a way to connect with the animal spirits, to tell them how much they were valued and respected for giving themselves to the hunters for food. This kind of hunting spirituality was important in order to give thanks. The animals would hear the songs and make themselves available again.

The Cree and other Indigenous Peoples have a different understanding of animals. We see that understanding in our stories and ancient myths, and it’s found in the hunting drum and songs. The animals have spirits and know when they are being mistreated or disrespected. It’s different than an agricultural view in which animals are domesticated and subservient to people. In the Cree way, animals, birds and fish are equal to humans and have souls. This is a fundamental difference in understanding our worldview, and it is often misunderstood.

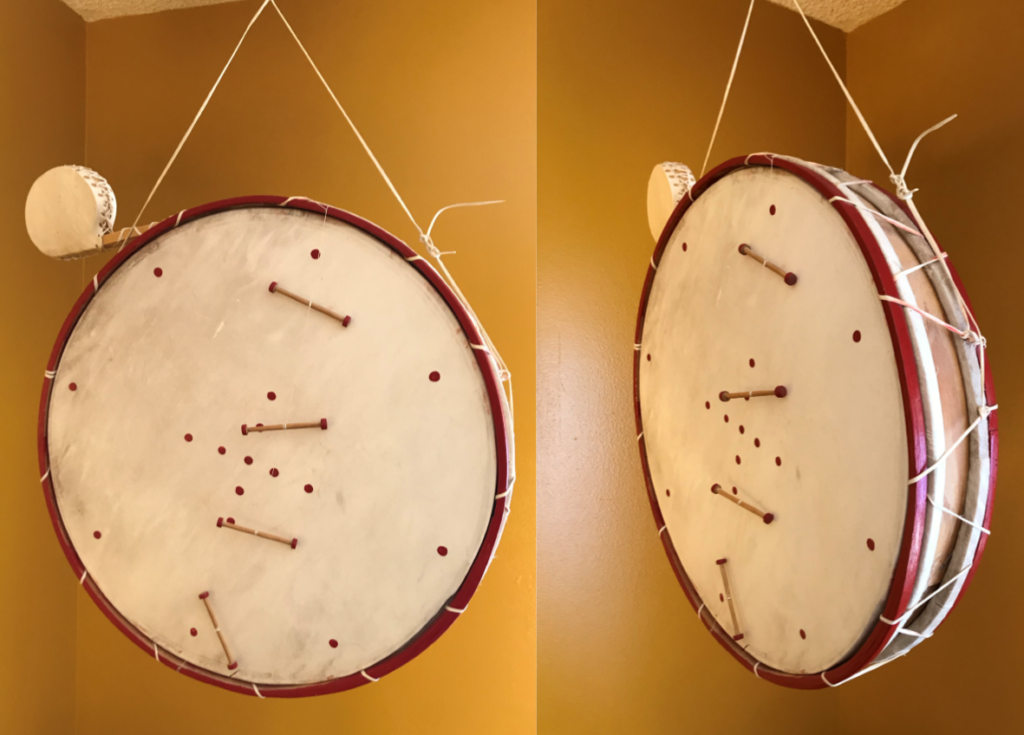

The Cree way of understanding, as well as the hunting drum and song, draws my interest today because it has survived over time and space and is a particular kind of self expression. While I don’t use the drum or songs in the way my ancestors did, I have respected the drum, cared for it, and kept it safe over many years. I carried it when I went to university and college, and it still hangs in my house today.

I consider it an original Cree way of expression that today we call ‘music’, but in the Cree traditional society of the past, it served a much different, deeper symbolic experience of life, death, and the inter-personal relations between humans, animals and the earth. It’s an Indigenous view, and one that even Cree youth and people of our communities have forgotten.

For myself, I have thought it important to understand Cree stories, ancient myths, and the hunting drum and songs of my ancestors. There are many different Indigenous practices and religions entering our communities today, and this is my way of preserving something of our Cree past.